The Moral Case for Government

Many principled people believe that the federal government is too far removed from everyday life to not screw things up; that they know what is best for them, and thus that the government has no place interfering in their lives.

Some view the government as inherently abusive, neglectful, ignorant, dangerous, and potentially out of control. It follows then, that we must protect ourselves from a government that may come after us at any time.

They believe that mature adults sink or swim by themselves, that we all must prove our responsibility and self-reliance; and that we are all competent and well informed enough to make our own decisions.

These are all intuitive positions. If you hold this mindset, you likely also believe that it’s just common sense that local governments always know how to spend money better than the distant federal government.

The US Capitol Building. Not always as scary and unhelpful as you might think!

Unfortunately, it ain’t true.

There are many, many things that are better done by government than the private sector, and better done at the federal level than the local level. And as a moment’s thought will demonstrate, living in a country with strong government and robust institutions—like America, Germany, Australia, Japan, or Denmark—enables much more freedom and human flourishing than living in a country without strong government and robust institutions, and the taxes that pay for them.

Countries such as Somalia, Rwanda, Tanzania, Bangladesh, Paraguay and Haiti are paragons of small government, with public sector employment between five and nine percent of total employment. The US has 15.8% public sector employment, while the OECD (developed world) average is 21.3%. Which of the aforementioned countries enjoy the most freedom, wealth, and human flourishing?

The Tennessee Valley Authority completed construction of the Norris Dam in 1936

A hundred different corporations or local governments acting separately can’t plan and execute an interstate highway system. They can’t design large water projects that benefit all, and neither they nor private entities have the will or capacity to create something like the Tennessee Valley Authority, which arguably rescued the region from the Great Depression and remains popular amongst both conservatives and liberals today. They don’t have the coordination or the resources to invent the internet, or fly to the moon, or eradicate polio. Just imagine if every airport had different standards and regulations that reflected ‘local’ sensibilities: the result would not just be chaos, it would be much slower and more expensive chaos. (You can see exactly this chaos in many parts of the developing world.)

The idea that all citizens are always competent and well informed enough to be best placed to know what’s in their best interest is also false. Firstly and most obviously, many people with mental health issues are not always competent enough to always know what’s in their best interests. But even those of us without mental health issues frequently lack both competence and enough information to know what’s always in our best interests.

Daniel Kahneman

The belief that we are competent and well informed rests on the assumption that all humans are perfectly rational—and have access to perfect information. We’re not, and we don’t. The Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler have shown conclusively that humans are predictably irrational in many ways, and that our cognitive biases (let alone our lack of information) consistently leads to poor decision-making. Concepts such as the following help to explain our consistent decision-making ineptitude:

- Loss aversion – the pain of losing is psychologically about twice as powerful as the pleasure of gaining.

- The endowment effect – occurs when we overvalue something that we own, regardless of its objective market value. Put more simply, people place a greater value on things once they have established ownership.

- Sunk cost fallacy – individuals commit the sunk cost fallacy when they continue a behavior or endeavor as a result of previously invested resources (time, money or effort).

- Hyperbolic discounting – present rewards are weighted more heavily than future ones. Once rewards are very distant in time, they cease to be valuable.

- Status quo bias – when people prefer things to stay the same by doing nothing or by sticking with a decision made previously. This may happen even when only small transition costs are involved and the importance of the decision is great.

You can read more behavioral science concepts here. Despite what we may like to think about ourselves, our competence is pretty limited, and we need enough humility to be able to acknowledge this. We can, have, and should, use government as a tool to help us to help ourselves make better decisions that overcome these inbuilt biases. Whether it’s making it easier for people to vote, easier for them to start a business, or easier to look after their health.

An independent individual

While respecting our individuality is vital to protecting our freedom, humans are fundamentally social animals—it is our ability to cooperate that has enabled us to reach far beyond the top of the food chain. Our government, and our institutions, are the physical manifestation of our democracy and our ability to cooperate. It is the mechanism by which the people’s will is expressed. It is not some alien “other”—government is made up of us, by us, and for us. It is how we pool our resources to achieve and access goods and services we could never achieve individually or by means of private corporations.

Everyone likes to complain about bureaucracy. But bureaucracy was originally brought into government to replace a system of uncontrolled corruption, political favoritism, and unconstrained lobbying. This is not to say bureaucracy cannot be improved. It is to say that the absence of bureaucracy can be—and often is—much, much worse than its presence.

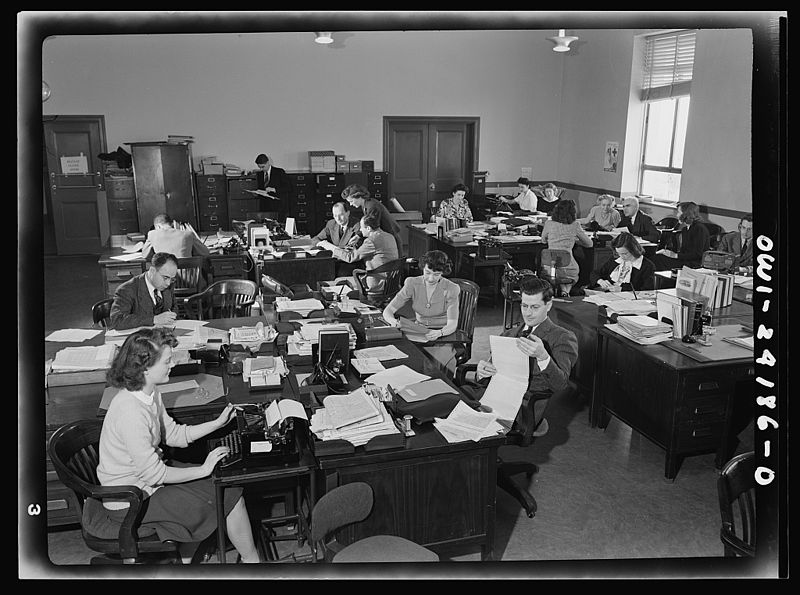

Bureaucracy: a thankless job, but we’re damn lucky to have people who do it

Ultimately the moral case for government is built around the principle of: “help, don’t harm.” Cognitive linguist and philosopher George Lakoff describes it in his book Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, as “an ethics of care, centering around empathy together with responsibility, both for oneself and others [that] is the moral basis of all the specific programs and issues.” It is only through government, and by building and maintaining robust institutions, that nations are able create the conditions for all citizens—rather than only the lucky—to flourish, look after themselves, and be the most free.